A key part of resilience is understanding how individuals, households, and communities will respond to a changing climate. In the Msimbazi Valley of Dar es Salaam, many people have become accustomed to flooding and take steps to reduce the disruption that floods cause to their lives. Practitioners who work with communities vulnerable to flooding suggest that people often take individual actions to reduce their risk, such as constructing small walls to prevent floodwaters from entering their home or building shelving to hold valuables out of reach of floodwaters. Other people plan to leave their homes during floods and stay with relatives or friends in the city. However, flooding is not the only source of risk for residents rapidly growing cities. The local government has struggled to manage the rapid pace of urbanization, and residents may experience difficulty finding work, affordable housing, adequate transportation, education for their children, or a number of other day-to-day needs. There has been no systematic study to understand the risk perceptions of households. This post explains initial research into this question and begins to explain how risk perceptions factor into the experience of risk and resilience in Dar es Salaam.

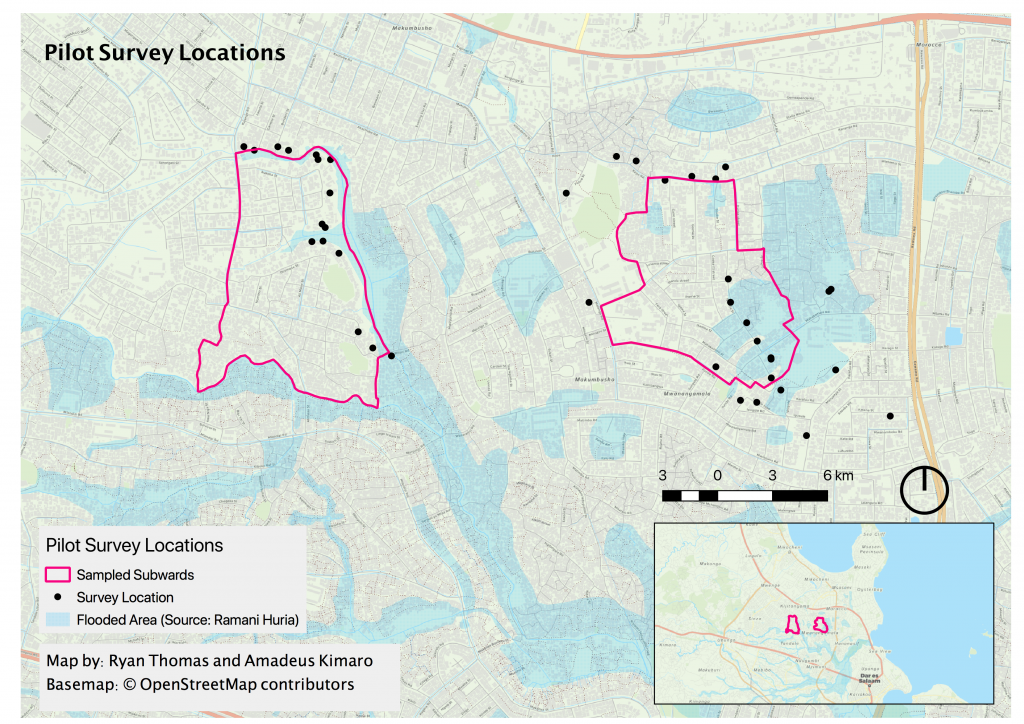

In February, the Resilience Academy research group piloted a survey in flood affected neighborhoods to begin addressing these questions. Ryan Thomas, a doctoral student in City and Regional Planning at Cornell University, and Amedeus Kimaro of Resilience Academy research led a team of students who had previously participated in the Ramani Huria data collection program to conduct the pilot survey. The team field-tested a new questionnaire using OpenDataKit and rapidly collected responses from people living in locations with a range of flood risk, including some residents experiencing regular flooding. We spoke with residents of two Mitaa (subward-level jurisdictions the size of large neighborhoods), Alimaua A and Msisiri B, to find out how they navigate, prepare for, and cope with risk. The survey covers a range of topics, including the main reasons that residents live in the neighborhood, their concerns about living there, and how they respond to and prepare for floods.

Results

We conducted 40 interviews, with 20 respondents reporting that they had experienced flooding in the past. Data analysis is ongoing, and the pilot is not sufficient to draw statistical conclusions. Nevertheless, we can report some results of the more straight-forward aspects of the survey. Below, we report results related to questions of housing tenure and reasons for living in the area, risk perceptions, and actions taken to reduce risk of flooding.

On average, respondents had lived in their homes for over 18 years and had long-term knowledge of neighborhood change. Out of the 40 respondents, 15 had received a certificate to right of occupancy issued by the municipal government (“title deed”), which is the strongest form of legal protection against eviction (though evictions can still occur). However, the rest of the respondents have some form of impartial tenure security, or no tenure security at all. Many respondents reported having obtained an informal license to construct housing from local community leaders, not the government. Respondents who have obtained a license to construct tend also to have lived in the area for a longer period of time than people who have a formal title deed. This may be due to the historical development of the neighborhoods, but we cannot tell why this would be the case from our survey. Many of the respondents live in the area because their family built the house (n=19) or because of the low cost of living (n=17). A smaller, but still significant number reported that they live in the area because of employment (n=11) and transportation (n=10).

Regarding respondents’ risk perceptions, or concerns about living in the area, increasing flooding was the most common response (n=27). Most respondents said that flooding is increasing (n=25), but a handful (n=4) suggested that flooding may be decreasing in their area. However, many respondents also discussed concerns about crime (n=14), growing population (n=10), and the cost of living (n=9). We did not ask about actions taken regarding these concerns, but that may be part of a larger scale data collection effort in the future. About one-quarter of the respondents (n=12) reported that they have taken increased measures to prepare for flooding in response to increased flooding. Many respondents who reported flood frequency increasing (n=25) also reported increasing flood depth (n=18) or remained the same (n=10). Those who reported flood frequency increasing were more likely to report adaptation than those who reported flood depth increasing, but more research is needed to find out if this result is significant or not.

Key findings

While the pilot survey was not large enough to make conclusions based on statistics, we still learned a lot about how people experience flooding. This pilot provided, more than anything, an opportunity to refine our survey questions and improve our methodology for collecting data so that a larger process will run more smoothly. While previous research demonstrated that flood frequency is increasing, this survey suggests that flooding is a major concern among residents in the surveyed areas, even among people who have not experienced flooding. This suggests a concern for neighborhood wellbeing beyond immediate household concerns.

Further work

This data collection activity will be scaled up in the coming months to cover more of the city and draw insights that policy-makers and community-based organizations could use to better understand how communities experience risk. By expanding the survey, we will be able to better understand the results and draw statistically valid conclusions. Additionally, we hope to expand the survey questionnaire and use other methods of research to understand how communities can respond collectively, as opposed to only studying the individual responses of households. This data may also be used to open discussions with local decision-makers about how citizens can participate in shaping a resilient future for Dar es Salaam.

Post written by Ryan Thomas and Amadeus Kimaro

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column] [/et_pb_row] [/et_pb_section]